A Gap in Specialty Coffee Industry

Since the concept of specialty coffee emerged, many coffee enthusiasts have put in significant effort and resources to promote it. But the question remains: has specialty coffee entered the public consumer market as a mainstream beverage, or is it still only popular among a small group of enthusiasts? From my observation, the answer leans more toward the latter. As a “true” coffee lover who has been working on UX for many years, I consider the coffee I make myself to be better than that made by some professional baristas. I think I have the legitimacy to say the following. I believe there is a “gap” between coffee suppliers and consumers. Some industry professionals are trying to make specialty coffee more accessible to the masses, while others are doing the opposite.

In the following, I will share my personal experiences to reveal this “gap” and trace its origins.

The Gap

The consumption of specialty coffee still primarily takes place in coffee shops, and even the most passionate home-brewed coffee enthusiasts wouldn’t pass up the chance to explore a new coffee shop. As important venues for exploration and discovery, the coffee drinking experience in cafes often begins at the counter.

First is the ordering process. Most specialty coffee shops still follow traditional practices, naming and categorizing their products based on brewing methods, such as Americano, Latte, Cappuccino, Piccolo, etc. Unlike traditional coffee shops, however, once a customer has chosen a product, specialty coffee shops will then ask the customer to select a type of coffee bean from a range of options. This is the most common ordering process in today’s specialty coffee shops.

Meanwhile, some coffee shops take it a step further, where customers select the brewing method after the coffee beans are selected. Personally, I strongly support this innovation that places greater emphasis on the value of coffee beans. However, most customers still order in the traditional way. I have often seen customers looking confused when they order a flat white or an Americano, only to be told by the barista that they can’t order that way. It’s said that some coffee shops are planning to use flavor profiles as the first step in the ordering process. Imagine that vast and branching flavor wheel—if the barista doesn’t guide the customer correctly, there will be even more confused faces. Of course, I’m not here to criticize the innovations made by cutting-edge coffee shops but rather to urge practitioners to consider customers’ habits and perceptions when introducing new concepts.

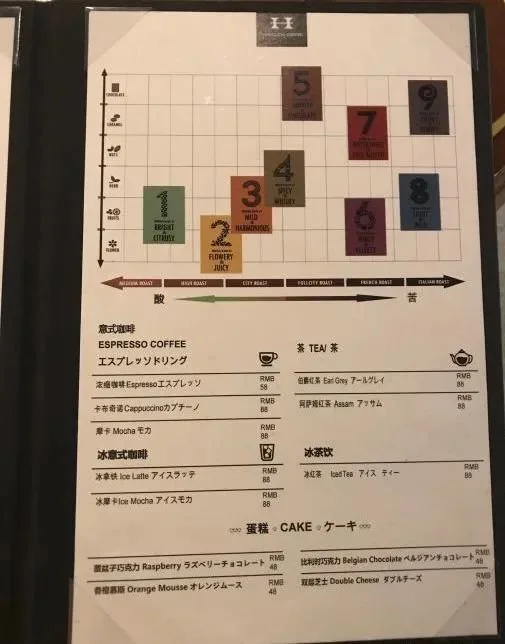

Reducing the barriers for customers when placing an order is crucial, and the design of the menu and proper guidance from the barista are especially important. There’s a Japanese coffee chain shop in Shanghai’s Bund area where the menu features a matrix as a guide for ordering. It took me some time to roughly understand this matrix and eventually ordered a No. 3 coffee. No. 3 is positioned in the middle of the roasting level axis, so I expected a fairly balanced flavor. But when the coffee arrived, it only had a very slight acidity. Upon closer examination of the menu, I realized that the zero point on the horizontal axis starts from medium roast. It turns out this coffee shop follows the traditional Japanese style and does not offer any light or light-medium roasts. In contrast, ordering at another nearby coffee shop (Arabica%) is much easier. Compared to the former, which offers 9 options, Arabica% provides only 2 options after the customer chooses brewing method: a regular medium-dark roast and a single-origin light-medium roast.

In specialty coffee shops, the proximity between customers and baristas often leads to conversations, especially during non-busy times. Once, I was at a very exquisite small cafe and ordered a pour-over that was said to be very sweet. The cafe was so small that it was inevitable that I would start a conversation with the barista. At that time, I had just learned about the chemical components of the extracted liquid from coffee beans which is called coffee, and I was very curious about the “sweetness” of coffee. I had always found it difficult to detect sweetness in coffee. So the conversation began with my question: “I recently learned that the sugar content in coffee is below the threshold of human taste perception. So what is the sweetness in coffee, and how can I perceive it?” To my surprise, this question seemed to offend the barista. He responded, “No, no, no. In fact, the sugar content in coffee is sufficient. People who cannot taste the sweetness of coffee need training. Their senses must be calibrated.” I didn’t let the conversation continue, but think: if consumers need sensory training to appreciate specialty coffee, then specialty coffee is indeed too far away from us.

The scenario described above is not an isolated case. Some baristas have very high expectations on their customers. My wife has often complained that the latte art on the surface of milk based coffee tastes bitter. This is because some very bitter substances get trapped in the crema of the espresso, and during the process of making latte art, the crema is almost completely retained on the surface of the coffee. I tried stirring the espresso with a spoon before pouring in the milk, but that didn’t help much. I then consulted a well-known coffee video blogger on how to reduce the bitterness on the surface of a latte. He told me to stir the whole cup of coffee before drinking. He believed that drinking without stirring is the wrong way to drink it, he asked me to teach my wife the correct way to drink it. But this method doesn’t work for those who are reluctant to stir because they don’t want to ruin the latte art. In coffee shops, it’s rare to see people “destroying” the latte art. Some even carefully sip the coffee, leaving the foam layer with the latte art intact at the bottom of the cup.

There are also baristas who no longer speak the same “language” as their customers. I once complained to a barista friend about a Nordic-style roasted coffee that I found “bland.” “No, no, brother, you’re mistaken. Light roast doesn’t necessarily mean bland. On the contrary, this coffee has very strong flavors,” he immediately corrected me. If I were a beginner or a customer just starting to try some specialty coffee, being “educated” like this would make me very uncomfortable. It was as if this barista friend was implying that either my senses were failing or my knowledge of coffee was inadequate. However, I wasn’t upset, because “bland” was my immediate, overall perception of that coffee. I didn’t break down my feelings into categories like aroma, flavor, or mouthfeel. “Bland” is a common term that any customer might use. However, to this barista friend, “bland” specifically referred to the intensity of the flavor. So I rephrased my words: “What I meant to say is that this coffee’s body is very thin. In terms of flavor, this coffee is extremely citrus-forward, lacking the balance that nutty or caramel notes would provide.” He then understood. Sometimes, communication really is challenging!

In addition to enjoying coffee in cafes, more and more coffee consumers are starting to brew their own coffee at home, not only satisfying their taste buds but also experiencing the joy of making coffee. Selecting and purchasing beans is the starting point of the home coffee-making experience.

When it comes to bagged coffee beans, poorly designed product information labels can be a significant barrier between the coffee beans and the customer. Flavor descriptions are the most important information on coffee packaging. Since it’s not possible to taste the coffee before purchasing, customers associate their sensory experiences with the descriptions on the label to imagine the coffee’s flavor. However, many roasters did not pay much attention on adding flavor descriptions. Some professionals might scoff at my statement, claiming they strictly adhere to the SCA flavor wheel or the WCR lexicon. But that’s exactly the problem. The SCA flavor wheel and the WCR lexicon are meant to be references, not standards. If they haven’t been refined, they may not even be suitable for use on labels. After all, who can imagine the taste of “butyric acid” or “isovaleric acid” without training? These aren’t things we commonly encounter in daily life. When labeling flavors, roasters need to break out of their professional mindset and consider the customer’s previous sensory experiences.

What’s more disappointing than being unable to imagine a flavor is when the flavors on the labels cannot be perceived when tasting. When I first started exploring specialty coffee, I often encountered this situation. At that time, I chose to trust the professionals who used cupping methods to identify flavors rather than relying on my own senses. Later, I gradually realized that this might not be related to my senses but rather a difference in brewing methods. The concentration of cupped coffee is lower, allowing the flavors to unfold more fully, which may reveal “surprise notes” that are difficult to detect in pour-over coffee. Additionally, the way professionals perceive coffee when cupping is different: “slurping” quickly distributes the coffee-air mixture over the taste buds. Customers do not do cuppings before enjoying their coffee, nor do they “slurp.” Therefore, I believe we should switch between two modes of thinking. When selecting coffee beans or pricing them, professional cupping can be used to reveal the flavor types and potential defects. However, when describing flavors, we should do it like ordinary customers, using the brewers they commonly use, taking small sips or big gulps like they usually do.

Speaking of coffee brewing, we need to talk about the impact of coffee-making equipment on the popularization of specialty coffee. I’ve noticed that when people talk about specialty coffee, they are more likely to think of pour-over coffee rather than espresso-based drinks. Personally, I think this is a good thing because making a good espresso is not easy, especially with very light roasts or beans with high density. Additionally, large and heavy espresso machines are difficult to bring into the homes of average consumers. Good machines are expensive, and poor ones are “difficult to tame.” French presses, pour-over drippers, and various small filtering brewing devices are the mainstays of home coffee-making equipment.

The misconception that “only professional equipment, or the equipment used by baristas, can brew good coffee” is common. French presses and some high-tolerance immersion-style brewers can effectively showcase coffee’s flavors, such as the Hario Switch, Mr. Clever, SIMPLIFY, Tricolate, etc. But why haven’t these brewing devices become more widespread? Is it that the word “specialty” in the minds of consumers only represents a certain brewing method? If so, who implanted this perception in their minds? I believe that the brewing methods used and endorsed by professionals have largely influenced customers’ perceptions. Many customers equate specialty coffee with pour-over coffee, bypassing simpler tools. In fact, many seemingly “foolproof” tools are perfectly capable of brewing coffee. “Tools” should not sit at the top of the value pyramid of specialty coffee. We need to make consumers aware of this. The widespread adoption of low-difficulty brewing devices can lower the threshold for enjoying specialty coffee, helping specialty coffee enter more homes. Eliminating the belief in “tool supremacy” requires the collective efforts of baristas, roasters, coffee bloggers, competition participants, and other professionals who can make a voice.

The Problem

Simply put, the specialty coffee industry is developing one-dimensionally, with this unbalanced practice being more focused on technology and technique rather than being consumer-centered or human-centered.

The current development of the specialty coffee industry is led by top professionals: knowledge and information flow from scientists to standard framers and competition participants, then to baristas, roasters, and coffee bloggers, and finally to consumers. In shaping the specialty coffee industry, the supply side has more influence than the consumer side. Within the supply chain, “technologism” is prevalent, with technical thinking dominating practice, and humans becoming mere agents of technology. In this context, coffee brewing has become a rocket science, and the interaction between water and coffee grounds has turned into a complex “physical” and “chemical” process. People have established various metrics to describe this process, continually using more “scientific” methods to make it more “transparent.” In this process, a new “language” has emerged—a “technical language” empowered by instruments, equipment, and tools. Those who understand this “technical language” might use a refractometer to describe the concentration of a cup of coffee in numbers, while those who don’t can only rely on their senses and use everyday language to describe the concentration. Gradually, the cognitive frameworks these two groups use to perceive things may become different. The former might see coffee as a certain amount of different compounds dissolved in a certain amount of water, while the latter simply sees coffee as coffee. More worryingly, the former often holds a “condescending” attitude towards the latter. Over time, communication becomes difficult, and an experiential gap begins to form.

After reading the above, you might think I’m a “Luddite.” In fact, I’m neither against coffee science nor against the technical approach. What I oppose is a one-dimensional technical perspective. In the pursuit of the best flavor and highest efficiency, many factors in the overall experience of enjoying coffee, such as values, attitudes, habits, emotions, and preferences, have been overlooked. I am very grateful to the scientists and professionals who have been expanding the boundaries of coffee, working to improve the “effectiveness” and “efficiency” for obtaining high-quality coffee. They must use scientific methods and technical approaches to achieve accurate, effective, and repeatable results. But the methods they use and the approaches they take are not suitable for those practitioners who need to interact with consumers. Now, almost the entire supply side has become technology-centered, without placing the human experience as the center of practice. The divergence between the supply side and the consumer side has led to a fragmentation of values and cultural contexts, and the lack of empathy is widening the experiential gap.

The Future

What does the future hold for specialty coffee? How should we popularize specialty coffee, and how can we develop the industry sustainably? I believe it’s time for a shift towards a human-centered approach, stopping the one-dimensional development. The key to bridging the gap lies in “empathy.”

Practioners and consumers are gradually becoming two disconnected groups, but “empathy” can help re-establish the connection between them. A blog post by Barista Hustle once discussed the differences in flavor perception between baristas and customers, and I strongly agree with their viewpoint. They suggested that baristas should abandon the “superior attitude” over customers and instead build empathy by understanding the “known vocabulary” of the customers, rather than “criticizing” or “educating” them. I believe that the goal of practitioners has never been, nor should it be, to showcase personal skills but rather to help customers find satisfaction in their hobby. To achieve this goal, empathy is essential. We need to actively listen, trying to understand their preferences.

Practitioners are not alone. Speaking of empathy, this is exactly where design could step in and help. By the nature of their work, designers are required to use two sets of languages: one is the “technical” language used to communicate with engineers, scientists, and professionals. The other is the “everyday” language used to communicate with consumers. As bilinguals, designers can act as a bridge, re-connecting practitioners with consumers, eventually eliminate the gap.